To say that my mother made lists would be a monstrous understatement.

Among her archive files, she kept shopping lists going back over decades of marriage and raising three children, noting the prices of everyday items. She kept lists of household tasks, outgoings, mortgage and utility payments and who had given which wedding present. She kept lists of her own and her children’s schools, teachers, exam results, certificates and sports or musical performances. She kept lists of the schoolchildren she had taught, and the names of the children and grandchildren of the growing families on her burgeoning Christmas card list. She kept list after list of craft projects, exhibitions, evening classes, art galleries, historical sites and theatre visits.

There are lists illustrated with sketches of birds, flowers, shellfish and butterflies seen on family holidays, and in the Malaysian jungle around Penang during the late 1950s where she served in the post-war colonial civil service. There is a folder thick with her epic lists of Christmas presents sent to family and friends, for every single year from 1955 to 2016 – the year when she died – six decades of devotion to keeping up connections.

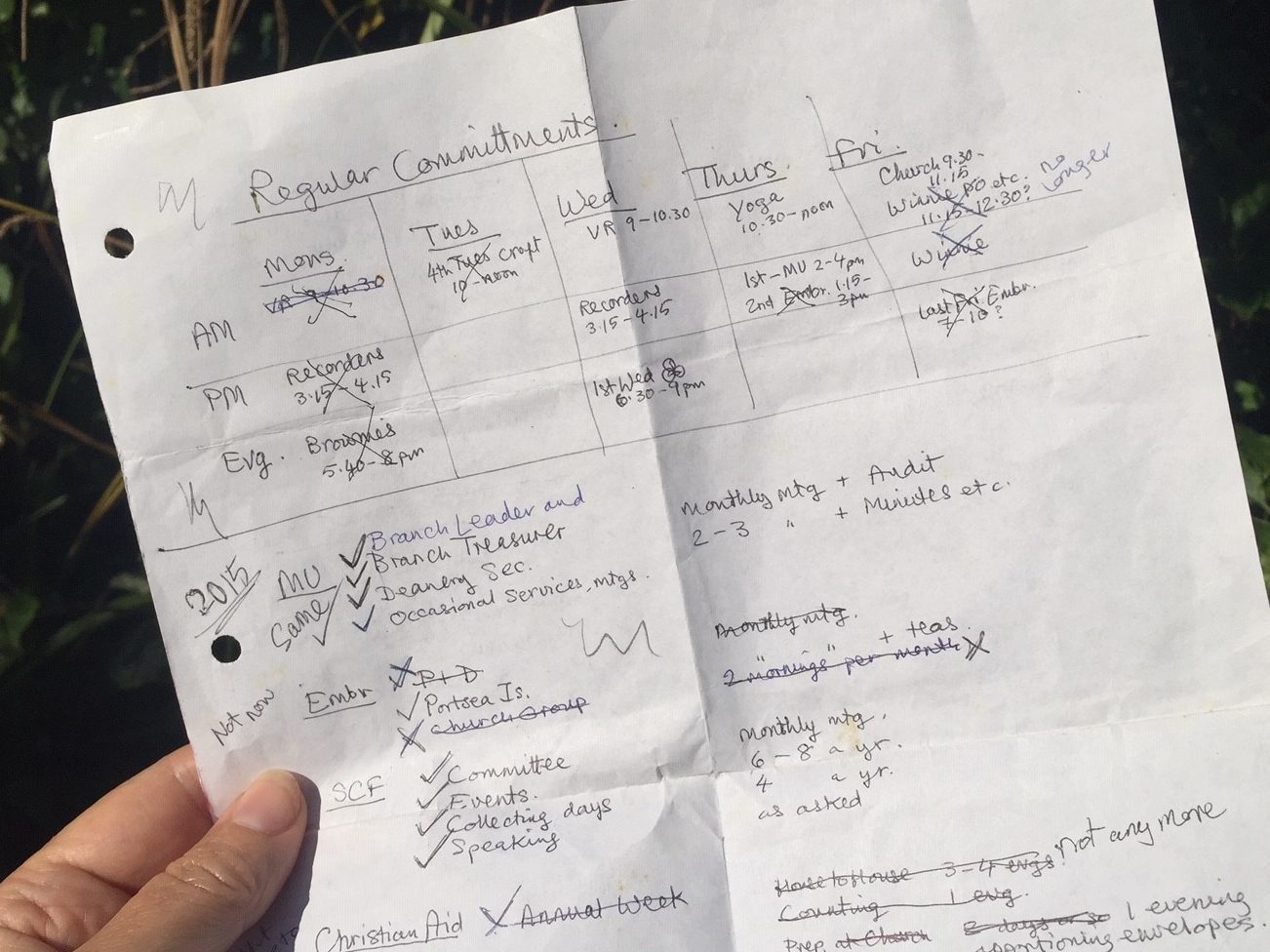

Among my mother’s very many papers, I found an A4 sheet setting out ‘Regular Commitments’ following her retirement from primary school teaching. A sketched chart of a typical week shows two committees; five sessions with a primary school, Sunday School and a Brownie pack to help children with recorder playing, craft, reading and learning the parables; church-cleaning; and weekly trips to the supermarket, post office and pharmacy for an elderly housebound friend. Listed below the chart are commitments over fortnightly, monthly and quarterly periods with the Mothers Union, Embroiderers Guild, Save the Children Fund, Christian Aid, Girl Guiding, Leprosy Mission and her church’s Sunday School. Her plethora of functional roles are listed, from District President, Branch Treasurer and sidesperson, to banner embroiderer, charity stall holder and chutney maker.

Several shades of pen and jotted dates suggest that she revisited the document a number of times, updating and amending this inventory of the support she gave to others. This list conjures a poignant visual memory. I see her in a woolly hat, scarf and gloves, standing in the cold outside Debenhams in the Portsmouth shopping centre, shaking a collecting tin for the Save the Children Fund as the shoppers come and go.

A later column of notes added in pencil is headed ‘2015’, the year before she died. Some items in the weekly chart have been crossed off in pencil. It shows that she was keeping up with a lot of her schedule, but dropping physical tasks that involved driving, working with larger groups of children, shopping for her friend or delivering charity envelopes from door to door. In her penciled handwriting I can detect an elderly wobble. She was troubled by carpal tunnel syndrome in her writing and crafting arm. By 2015, the early signs of unacknowledged dementia were also perhaps beginning to show.

When she writes these lists, who is she communicating with? Hers was the instinct of a family archivist and inveterate collector. Exam certificates, children’s names, committees, trips, bird and shellfish species, Brownie badges and embroidery techniques, continuously noted and reviewed. Years later, I now serve as her belated witness, but when she wrote these lists she had no expectation of an audience (except perhaps St Peter receiving her accounts of good deeds). These are not lists of things that needed to be done, but things that were being done – evidence of action and experience. She was serving as her own witness – a profound expression of “this is what it means to be living,” “my experiences matter,” and “I exist”.

Precious few other people noticed and appreciated what she did. My father told me not to mention such things in her funeral oration, being largely female and therefore automatically irrelevant, but I did anyway. I think about her household and her marriage, and see so much fundamental and unacknowledged hard work. I also detect solitariness. Coupled with the livid anger and control from their father, her sons – my brothers – found the whole set-up oppressive and left home decisively, never to return. One kept nothing (definitely not lists); the other mainly the photographs and a few selected mementoes of foreign travel. Neither will talk about their childhoods, not even to their wives. I stayed on and did my very best to be her loving witness, participating in her charity work, craft-making, re-living her childhood, and her obsessional relationship with gift-giving. I stopped short at the door of her church, having by then little respect for father figures – ordained, deified or by procreation.

When she died, my devastated father sat sifting helplessly through her drifts of papers and saying, “I had no idea how much she did.” Too bloody right.

On the back of the A4 sheet of ‘Regular Commitments’, she wrote another list in biro, titled ‘Home things done weekly’, much more in the genre of ‘to do’:

- Washing

- Drying

- Ironing

- Bathroom cleaning and floor wash

- Kitchen cleaning and floor wash

- Catering

- Shopping

- Cooking

- Washing up

- Tidying

- Rubbish, recycling and composting

- Changing the bed sheets

- Sweeping the porch, conservatory and paths

- Gardening and watering

Each item has a penciled tick beside it, possibly added in 2015 to show that in the final year of her life, in her wobbly 80s, she continued to run the household whilst my father watched his incessant TV, collated his own lists of genealogical research and World War medal winners, sorted his stamp collection, had several extended hospital stays, did a bit of the gardening and washing up, demanded a 6pm dinner every evening and became increasing irascible.

When she died, he paid somebody else to do most of the stuff called ‘Home things done weekly’. If I had lived nearer, this ‘to do’ list would have been passed to me because I am female. But by then I lived in another city and had my own list of things to do, with the additional consuming tasks of ‘full-time job’ and ‘child-rearing’, both of which she – of course – had already completed with supreme devotion, the latter in triplicate.

At the very end of my mother’s A4 sheet of ‘Regular commitments’ there are two final items:

- All gift and card buying (family and friends)

- All wrapping, posting

I am drawn to the word ‘all’. Do I detect a whiff of resentment? These are home tasks that ought not to be chores. Shouldn’t they be for pleasure, mutual appreciation and celebration? Yet she had so little support in the preparation for and enjoyment of special occasions. What changes would it have taken for these to have been listed in a way that expressed not just “I exist”, but “We exist,” “We are family,” and “We do this with pleasure and together”? Sixty years of epic lists of Christmas presents bought, wrapped and posted, for three children and for his family and friends as well as her own. She did it all and prepared all year. He would rush out every Christmas Eve to buy a last-minute box of Thorntons chocolates, which he would hand to her the next morning still in its plastic bag. The only Christmas present I remember him buying on his own initiative for me (memorable because the act was such a surprise) was a large tin of chickpeas wrapped in a page from the newspaper.

I bear witness that my mother’s lists were her evidence of the indefatigable effort and devotion she put into experiencing, remembering, getting things done, keeping up connections and helping others. I raise my writing and crafting hand in honour of what she and so many women do to keep the world afloat. Blessed are the list-makers.